Do the Voices of Victims of Mass Atrocities Make a Difference?

The sombre speeches of foreign dignitaries including the UN Secretary General and heads of state were interrupted by sobs and screams from the thousands packed into Kigali’s Amahora stadium. It was 2014 and we were marking Kwibuka20, the Rwanda genocide’s 20th anniversary. Red Cross volunteers clambered along the stands to stretcher away the dozens fainting around us. I was back in the stadium I had first visited in 1994 to meet the failed UN peacekeeping mission headquartered there. What could I hope to learn by returning? The purpose of learning is to imbibe knowledge that creates understanding, generates insight, and triggers empathy. Ultimately, that aims to improve individual and societal attitudes and behaviours. That was the motivation, in this context, for listening to genocide survivors. The same objective has spurred the growth of Holocaust education in the aftermath of Nazi Germany’s progrom against Jews during the Second World War. But at a time that antisemitism and other hatreds and divisions are at record level, is it working?

Of course, it is inherent in the human condition to fail again and again. And so, the Holocaust was preceded by the Ottoman Empire’s Armenian genocide and German Southwest Africa’s Herero and Nama genocide. And succeeding it were the Rwanda, Srebrenica, Cambodia, Yazidi, and Darfur genocides. Not to mention genocide-like atrocities against the Uyghur in China and Rohingya in Myanmar, or in Ethiopia’s Tigray region and Gaza.

Meanwhile, for millions elsewhere, such as the fast-fading survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or today’s Afghan and Iranian women, and the record numbers of people mired in brutal conflicts, it is of no utility to debate whether or not their suffering satisfies legal definitions of genocide. The evidence is that the horrors that invite us to make earnest vows of “never again” always happen again and again. So, why do the survivors of abuse and atrocity bother to re-live their trauma by sharing their stories? For example, with the former prisoners of Syria’s Assad describing their gruesome torture experiences.

Psychologists say that talking about their ordeals helps survivors to heal. That is probably so in private individual or group therapy sessions. Presumably that is happening with released Israeli hostages, and perhaps with some Palestinian ex-detainees lucky to access mental support. But why do many victims broadcast their pain to the world, including intrusive intimate details? They say that they are trying to console those suffering alone or in silence. Or they speak up to prevent the suffering of future victims. These are noble intentions.

But there is also a worrying side to speaking-up through the parallel growth of a reparation and compensation culture. As if that can cancel all endured insults and injuries. That may, instead, create permanent victimisation hindering rehabilitation and recovery. I got a more compelling answer from a woman in Sudan’s Blue Nile state a few years ago. While I tried to preserve her privacy interviewing her on camera, she cast aside her veil to say, “look at me and tell the world my story. What is the point of being born here, getting raped, and dying here, with no one knowing?” Her defiance was a search for personal meaning for her suffering. Why did such bad things happen – and why to her? That is a much more difficult question to address than the lofty abstraction of global genocide prevention.

The quest for meaning underlies Heidi Kingstone’s recent book on ‘Genocide: Personal Stories, Big Questions’. This is a gripping journey across space and time through the thoughts and feelings of those who have found themselves at the frontlines of inhumanity. Fortunately, we are spared trite answers or simplistic explanations around the mechanics of genocide that are beloved of some experts. The reality, as Heidi illustrates, is that evil descends in many, and often unpredictable, forms. Thus, heeding the diverse voices of those who experience it is the best way to prepare. Perhaps that is also why the memorialisation of genocides and mass atrocities has become big activity, with numerous commemoration days in our calendar.

Such remembrances are well-meant but can be opportunities for virtue signalling by self-serving politicians or they get misused by those bent on polarising public opinion yet further. Thus, it is commendable that Poland’s Auschwitz Museum asked visiting world leaders to keep away from the microphone at this year’s Holocaust Memorial Day on 27 January. This marks the historic 80th anniversary of liberation of the iconic Auschwitz concentration camp. Instead, Auschwitz survivors are centre stage with added poignancy as time and age is fast diminishing their ranks. When they are all gone, who will have the credibility to inspire future generations not to repeat past horrors?

Fortunately modern technologies come to the rescue, not just through the digitisation of testimonies but by bringing them to life through augmented and virtual reality reconstructions. That is a good stratagem to lure the passive observer into involvement. As said by Auschwitz survivor, Elie Wiesel, “When you listen to a witness, you become a witness”. Wiesel got a well-deserved Nobel Peace Prize in 1986 for his lifetime service as a “messenger to mankind”. His vivid writings compel people to stare evil in the face, as in this excerpt from his memoir: “Never shall I forget the small faces of the children whose bodies I saw transformed into smoke under a silent sky”.

Countering the inexorable passage of time that blunts memory and tempts denial of our worst misdeeds, is what keeps Holocaust and Genocide Museums busy. Such as the Shoah Foundation at the University of Southern California, chaired by Steven Spielberg. His epic film, Schindler’s List, around the true case of a Nazi becoming a humanitarian, has had profound inter-generational impact. The Foundation’s enormous collection of survivor testimonies – 56,000 stories in 44 languages across 65 countries – strives to inform a future that rejects prejudice, hatred, dehumanisation, and genocide.

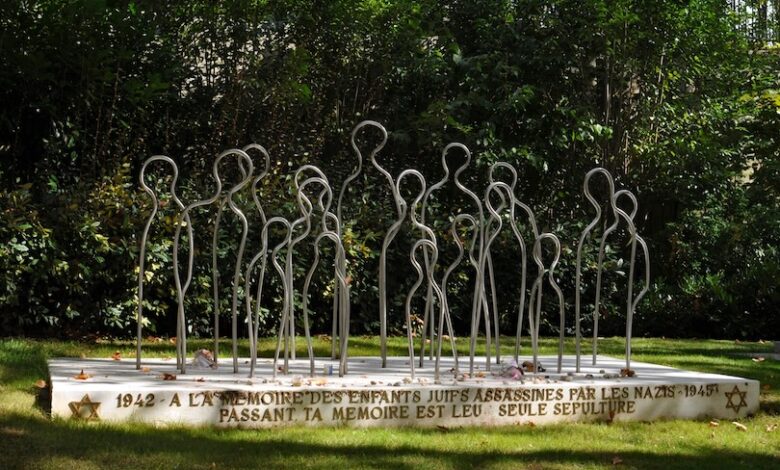

Elsewhere, survivors – and perpetrators – overcome identity-based violence, practice at reconciling, and take some peace home by visiting the Kigali Genocide Memorial, located at the final resting place of 250,000 slaughtered people. With similar intent, Cambodia’s Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum preserves extensive records in a former prison and torture centre. The Srebrenica Memorial Center curates the personal stories of genocide victims buried in mass graves. Major genocide museums, as in Illinois, Washington DC, Paris, and Berlin maintain powerful information centres and conduct extensive research and outreach. Most of us are personally unable to travel to these shrines to human cruelty. However, with virtual tours available, all can visit online. The “hear no evil, see no evil” excuse to avoid learning directly from the mouths of those who suffered most, is no longer valid. That is an important consideration in our age of proliferating misinformation.

Of course, these efforts do not stop recurrent inhumanities. But as we grapple with that challenge, at least a signal is sent to duty-bearers who continue to fail to act. Also to bystanders who look away or walk past and, therefore, condone wrongdoing. Neither of them can benefit from the alibi of ignorance. Victims of mass atrocities say that this gives them a modicum of comfort even if, on current trends, their struggle for accountability and justice is largely frustrated. However, more debatable is whether the raised voices of victims serve to shame and check perpetrators or, conversely, feed their sense of impunity.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

https://www.e-ir.info/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/shutterstock_2352907041.jpg

2025-01-27 07:49:11