Brussels Show Offers Diverse View of Art History — Global Issues

BRUSSELS, Mar 04 (IPS) – It’s like walking through several psychedelic halls of history, where bold colours, electrifying compositions and contagious rhythms hit the senses all at once.

This is When We See Us: A Century of Black Figuration in Painting – a momentous exhibition running at the Bozar Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels, Belgium, until Aug. 10, 2025.

The show places African diasporic art firmly within the global sphere of art history, bringing together some 150 luminous artworks from the past 120 years, by Black artists worldwide who explore daily life and other topics.

“One of the most enduring features of the human condition is the inexhaustible desire to see oneself through visual culture and storytelling,” said Koyo Kouoh, co-curator of the exhibition with Tandazani Dhlakama, and executive director and chief curator of Cape Town’s Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (MOCAA) – which conceived and organized the exhibition.

“Whether living on the continent or within the vast, impressive African diaspora, Black artists have invested in a spectrum of narratives that encompass the experience of blackness, intentionally rejecting limiting tropes of representation,” Kouoh told journalists as the exhibition opened in February.

According to Zoë Gray, Bozar’s director of exhibitions, When We See Us demonstrates how art history is “plural, diverse, and always intertwined”. She said that when she first saw the exhibition in South Africa, she immediately wanted Bozar to host it as well. (The show has now travelled from MOCAA to Basel, to Brussels. It will move on to Stockholm in October for a 10-month stint in the Swedish capital.)

The paintings – from a timely “insider” perspective – are grouped into sections titled “The Everyday”, “Repose”, “Triumph and Emancipation”, “Sensuality”, “Spirituality”, and “Joy and Revelry”. As visitors wander through these sections, they stroll to an accompaniment of global rhythms (arranged by musician and sound artist Neo Muyanga); and the overall effect is of a lively, panoptic world.

A feature of the display is the “interconnectedness”, or “inter-generational similarities”, among artists and art styles across the African diaspora. The organizers highlight, for instance, the commonalities between an iconic African American artist such as Romare Bearden (1911-1988) and a South African artist like Katlego Tlabela (born in 1993), by placing their works in juxtaposition.

But this is just one noteworthy element. When We See Us can be viewed as an historic art journey, a parade of artistry, a different way of seeing, an explosion of joy.

The curators say the show’s title is “inspired and derived” from the 2019 miniseries directed by US filmmaker Ava DuVernay, When They See Us, which depicts systemic racial prejudice and violence.

“I like shifting things and flipping things … as a way to continue the conversation,” Kouoh said. “So, flipping ‘they’ to ‘we’ allows for a dialectical shift that centres the conversation in a comparative perspective of self-writing, as theorized by Cameroonian political scientist, Professor Achille Mbembe.”

She said it was important for the organizers to show a plurality of experiences and to avoid “reductive” and “myopic” narratives. Pain and injustice are not at the forefront of this exhibition, as black experiences can also be seen “through the lens of joy”.

As for the choice of figurative painting, this reflects the history of the genre throughout the world and especially amid Black artistic practice, she remarked.

When We See Us naturally represents a range of countries and regions, with paintings from the African continent, Europe, North America, the Caribbean, and Latin America. The canvases include a gamut of large-scale paintings – work by Kudzanai-Violet Hwami and Cornelius Annor among them – as well as smaller creations such as the introspective “The Reader” by William H. Johnson.

Many of the artists have lived in different places and reflect an array of influences or associations; Cuban-born Wifredo Lam, for example, was a long-term resident of Paris, and died there in 1982. He was friends with Spanish artist Pablo Picasso, associated with other European artists including Henri Matisse and Joan Miró, and knew Mexican artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. In the exhibition, visitors get to see Lam’s striking 1938 work “Femme Violette” up close.

Meanwhile, works by the “kings of Kinshasha” – Congolese artists Chéri Samba and Moké – stand out for their audacious, animated canvases, as well as their satirical themes.

“They were both pivotal protagonists in the political provocative Zaire School of Popular Painting, a style that developed in Kiinshasha in the 1970s, a decade after Congo’s independence from Belgium in 1960,” state the curators. “The work of both artists was focused on the daily life in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo.”

(For a profile of Chéri Samba see: Congolese ‘Kings’ of Art on Exhibition in Paris)

Emerging artists are shown with established painters too, and several young artists were present alongside their work at the exhibition’s opening.

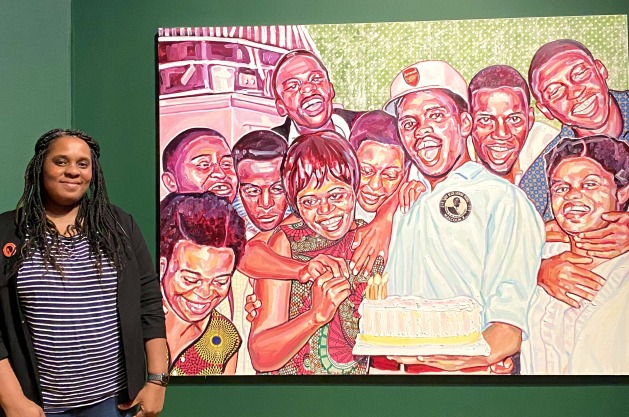

In the section “Joy and Revelry”, Netherlands-based British-Nigerian artist Esiri Erherienne-Essi said she wanted to show a different side of anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko. Her painting “The Birthday Party” depicts a group posing for a photograph at a joyful event. Here, she centres a happy-looking Biko, celebrating his niece’s birthday.

In her work, Erherienne-Essi uses photographs from historical archives as a starting point to create her paintings, according to the curators. She brings to the fore “archives and moments from Black people’s lives with vibrant depth, colour and detail, countering the flatness of the Black figures in the Western art historical narratives,” they added.

This idea of reversing the gaze is central to When We See Us – especially in the section “Sensuality”, where artists explore “various levels of pleasure, leisure and desire” with works in a variety of media. Among these, the remarkable “Never Change Lovers in the Middle of the Night”, by American artist Mickalene Thomas, employs acrylic paint, enamel and rhinestones to depict sexuality.

All the artworks are arranged in such a way as to make visitors feel fully connected to the paintings, said Ilze Wolff, of Cape Town design firm Wolff Architects, responsible for the exhibition’s scenography. Visitors can sit in some sections and become immersed in a particular set of paintings.

Then, emerging from this universe, they are invited to explore further, as the exhibition also offers a timeline, a video archive, and a documentarian area, with a wide selection of books. (The timeline’s starting point is 1805, just after the Haitian Revolution, and it details other important events that have shaped black art history, including the Négritude movement and the Harlem Renaissance.)

“MOCAA calls this the ‘brain’ of the exhibition,” said Maïté Smeyers, Bozar’s Curatorial Project Coordinator. “In association with the timeline, the curators wanted to have this documentation room, where they’ve put all the important writings on Black art and on the artists that are in the show. We’ve also included some literature, poetry, and other work by African diaspora writers because this has a role in the Black arts consciousness, and it contributes to the Black art movement, the history and the shaping of the fields.”

Visitors can freely browse some 80 books, loaned by Belgian institutions including the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), local library Muntpunt, and art galleries.

“The books on display give a glimpse of the history of research into Black art, as well as of Black literary writing, philosophy, and political thought,” said Eva Ulrike Pirker, VUB professor of English and comparative literature. “While the exhibition is temporary, the books, including the beautiful catalogue, which offers reproductions of all the artworks, are in Brussels to stay and available at the partner libraries free of charge.”

Pirker said she liked the idea that the exhibition will have a “concrete, lasting impact” on the collections of libraries that have partnered with the show, as it prompted librarians to look into their holdings and acquire new books to fill existing gaps.

Showing the richness of African diasporic art, the documentation section may even spur viewers to seek out more information, as well as related artwork.

“When We See Us is about a historical continuum of Black expression, Black consciousness and joy, and we hope (audiences) will enjoy it,” said co-curator Dhlakama. – AM/SWAN

© Inter Press Service (2025) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

https://static.globalissues.org/ips/2025/03/whenweseeus.jpg

2025-03-04 21:24:23