Celtics

In Boston.com’s bracket of the 16 best trades in Boston sports history, Auerbach authored three of them himself.

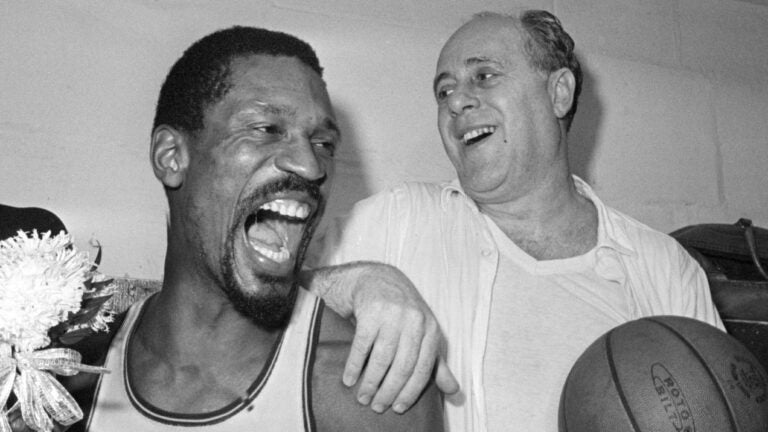

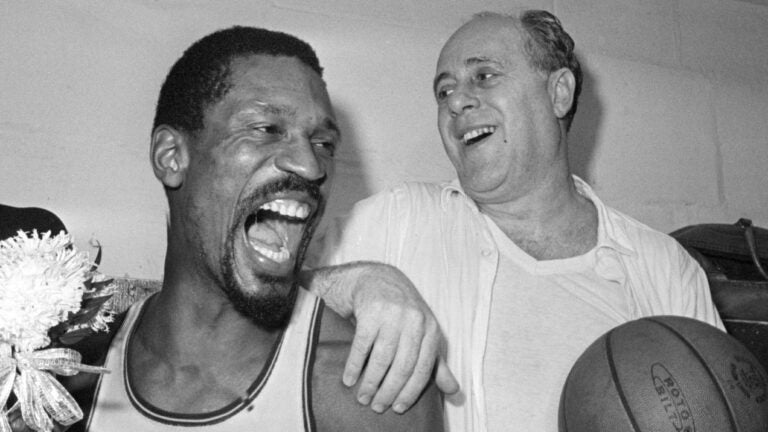

As he lit one of his characteristic cigars while pondering a question during a 1983 interview, Red Auerbach reflected on a pearl of personal wisdom that — given his history — may have felt decidedly uncharacteristic.

“Many times the best deal is no deal,” said the longtime Celtics president. Holding the cigar in the same hand on which he wore one of his (then) 14 NBA championship rings, he leaned back in the leather chair of his Boston Garden office — adorned with memorabilia reflective of his central role in an unprecedented basketball dynasty — and offered a discerning critique of his peers.

“A lot of people in sports make trades to satisfy their own ego, or just to make a trade, rather than actually helping their ball club.”

Auerbach, though he may have concluded that “no deal” was preferable more often than not, was nonetheless defined by the trades he did make. And in that regard, the benchmark he set is a standard unlikely to ever be matched. In Boston.com’s bracket of the 16 best trades in Boston sports history, Auerbach authored three of them himself:

- 1956: Traded Cliff Hagan and Ed Macauley to the St. Louis Hawks in return for Bill Russell (the second overall pick in the 1956 NBA Draft).

- 1980: Traded two 1980 first-round picks to the Warriors for Robert Parish and a 1980 first-round pick (Kevin McHale was later selected).

- 1983: Traded Rick Robey and two 1983 second-round picks to the Suns for a 1983 first-round pick, a 1983 third-round pick, and Dennis Johnson.

Of those trades, none resonate through time like the Russell deal.

Though the rumored involvement of the Ice Capades in the negotiating to get Russell was undoubtedly an apocryphal tale, the deal itself remains a masterpiece of foresight.

Ahead of the ’56 draft, Auerbach knew his team was good but by no means great. Boston in the early 1950s was a consistent playoff team, but fell short each season to either the Knicks or the Syracuse Nationals.

While the decision to acquire Russell seems obvious in retrospect, it was an aggressive trade at the time. Ed Macauley, who Auerbach dealt to St. Louis to get the second overall pick (which the Hawks had used to pick Russell), was in the midst of a run of six straight All-Star appearances. He was in his late twenties, seemingly the prime of his basketball career.

Yet Auerbach kept his focus on “actually helping the ball club,” deciding that the possibility of adding Russell’s potential (especially on the defensive side) outweighed the risk trading a known quantity like Macauley.

It’s a classic dynamic that general managers and front office personnel have grappled with for decades (both before and since), and it proved foundational to Auerbach’s legacy, and the establishment of the Celtics as the league’s premier team.

The second player dealt to St. Louis in the Russell deal was Cliff Hagan, another testament to Auerbach’s vision. Hagan was a star at the University of Kentucky, but ended up playing another year at the college level even after he was picked in the third round by the Celtics in 1953 (as the school had sat out a season following a point-shaving scandal in 1951).

Hagan then joined the U.S. Air Force for two years, but his NBA player rights remained with the Celtics. So despite never putting on a Boston uniform, Hagan was a valuable bargaining chip that Auerbach managed to hold onto until the moment arrived when he could be most effectively used.

Hagan went on to a Hall of Fame career in his own right, demonstrating that the Russell deal — lopsided as it clearly was in the Celtics’ favor — was not a robbery.

The example of Hagan also highlights another staple of Auerbach’s style. That along with being a great assessor of talent and potential, and understanding the prevailing chemistry of a team (knowing, as he had put it, when “the best deal is no deal”), was his creativity.

As his peers scrambled to trade for established stars to compete with his current Celtics teams, Auerbach was always looking for the next thing. With each success (and championship banner), finding and acquiring future stars became increasingly difficult, yet the wily, cigar-toting executive remained multiple moves ahead.

When meddling Celtics owner John Y. Brown pivoted without his knowledge and traded three first-round picks for Bob McAdoo in early 1979, Auerbach turned the crisis into an opportunity to do something even bigger.

Seizing on the specific rules of NBA free agent compensation, he utilized Boston’s signing of Pistons free agent M.L. Carr as a means to trade McAdoo to Detroit in Sept. 1979.

“We acquired M.L. Carr via free agency (in 1979) in the point in time when there was compensation that would be due when you signed a free agent player,” former Boston general manager Jan Volk told Boston.com in a 2017 interview.

“The two teams would get together to essentially hammer out what would’ve been a trade for that player,” said Volk. “In a situation where the two teams couldn’t agree – which happened fairly regularly – there was a mechanism for appealing to the commissioner for an expedited compensation hearing where the commissioner would impose a trade. And that’s what happened with us.”

Eventually, Boston was able to push Detroit into agreeing to take McAdoo as compensation. But in addition — and because the Pistons had failed to pay Carr a previously agreed bonus — the Celtics also worked out a deal in which the team received two first-round picks.

One of those picks eventually turned into the No. 1 overall selection in 1980 (as Detroit fell to a league-worst 16-66 record), which Auerbach then shipped to the Warriors as part of the deal to acquire Parish and draft McHale. It was a complicated series of transactions for its time, but it netted two Hall of Famers.

Other examples abound, especially in the 1970s/1980s era of Auerbach’s tenure. Picking Larry Bird in the draft while he still had another year of college eligibility was highly unusual, but landed Boston another MVP. Taking a second-round flyer on college star (and Toronto Blue Jays prospect) Danny Ainge eventually netted Boston another dynamic player even though it required the unorthodox court fight against a team in another league.

In a time when other NBA executives were making trades to, as Auerbach noted, “satisfy their own ego, or just to make a trade,” he was approaching the concept of roster building from an almost modern point of view, squirreling away assets and then deftly deploying them at the right moment to ensure the acquisition of the right player.

In the end, he built 16 champions across four decades. It remains a peerless run by a single basketball coach or executive. No one in his role ever did more in “actually helping their ball club.”

Sign up for Celtics updates🏀

Get breaking news and analysis delivered to your inbox during basketball season.

https://bdc2020.o0bc.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Red-Auerbach-Best-Boston-trades-1-67e03eeaa05cc-768×432.jpg

2025-03-23 12:32:14